The term "human remains" has varying meaning from one culture or institution to another. It can refer only to body fragments or skeletons, to grave goods associated with human bodies, or even to artifacts that are comprised, in part or in whole, by fragments of human bodies.1 The collecting, preserving, and displaying of human remains has been controversial for millennia, as long as human bodies have been publicly displayed. Human bodies can serve as vital sources of information that allow us to learn the history of our ancestors and of our communities. As early as the 14th century, human cadavers have been studied for anatomical knowledges and human developments; until this day, they continue to benefit us with pathology and etc. Therefore, museum displays of human remains are seen by many as a vital source of knowledge and providing visitors with a connection between the past and the present.2 Ongoing debates regarding whether human remains should be displayed or how they should be displayed reveal concerns on the part of experts and members of the public alide. These concerns span a wide range of perspectives and can be ethical, religious, or societal. The discussion involves disparate groups including religious communities, related descendants, curators, archaeologists and museum visitors.3 Some argue that displaying the dead simply fulfills the curiosity of the living, while others believe it is disrespectful to the deceased, violating religious beliefs and practice.4 The public display of human remains inevitably objectifies human bodies, leading many visitors to forget that these "objects" were once living humans, sons and daughters, husbands and wives, mothers and fathers. Cadavers have become a mixture of flesh and science in modern society. They are examined and studied by professionals, then put on display for the public. Endlessly pliable and forever manipulable, even after death. Eventually, the controversies surrounding the display of human remains in public institutions refer to the essential question of whether the needs of the living should surpass those of the deceased.5 An exploration of two case studies may help resolve these questions.

Mummies at the Manchester Museum

Ancient Egyptian mummies are, arguably, the most common type of human remains most visitors see in museums. For centuries, ancient Egyptian mummies and their related grave goods have been looted, illegally exported, and displayed in museums around the world. Body Worlds notwithstanding, they are the most popular displays of human remains as they provide a glimpse into lives over 2000 years ago. For example, King Tut's mummy has generated the largest viewership in the history of museum exhibitions.6 However, with the awakening social awareness, more and more people realize that bodies in museums have been removed from their place of burial and are recontextualized for different functions.7 A near universal human instinct to treat the dead with respect comes into direct conflict with the public's desire to view mummies.

The possession and display of these most ubiquitous of human remains is both expected and accepted by museum visitors. In the long history of display, mummies, as a form of human remains, have become a quintessential "museum object", one that represents both history and curiosity. Nevertheless, the debate regarding how to respectfully display human remains everpresent. Due to public complaints, in May 2008, the University of Manchester's Museum of Manchester conducted an experiment to determine the most appropriate way to display the ancient Egyptian mummies in its collection based on public opinions.8 The three mummies involved are the unwrapped Chantress Asru, the partially unwrapped male mummy known as Khary, and a mummy of a child. Before 2008, they had been displayed as naked, mummified bodies; however, during the experiment, they were covered from head-to-toe by white cloths before the announcement of the final decision.9 Members of the public were consulted in meetings and other means of feedback, which was then shared with the museum's Human Remains Panel.10 The final decision of the Panel was that the mummies would remain on display but with clothes covering their genitals.11

Aside from museum professionals and scholars, the public especially people from the Manchester community also supported the mummies to remain on display at the Manchester Museum. Karen Excell, who was the curator of the Egyptology collection and a member of the Human Remains Panel, studied the responses from the public on the museum websites.16 The majority of posting all disagreed with the cover of the mummies, and questioned how people could be inspired or became interested in Egyptology and history in general when the legacy of that history was being hidden from view.17

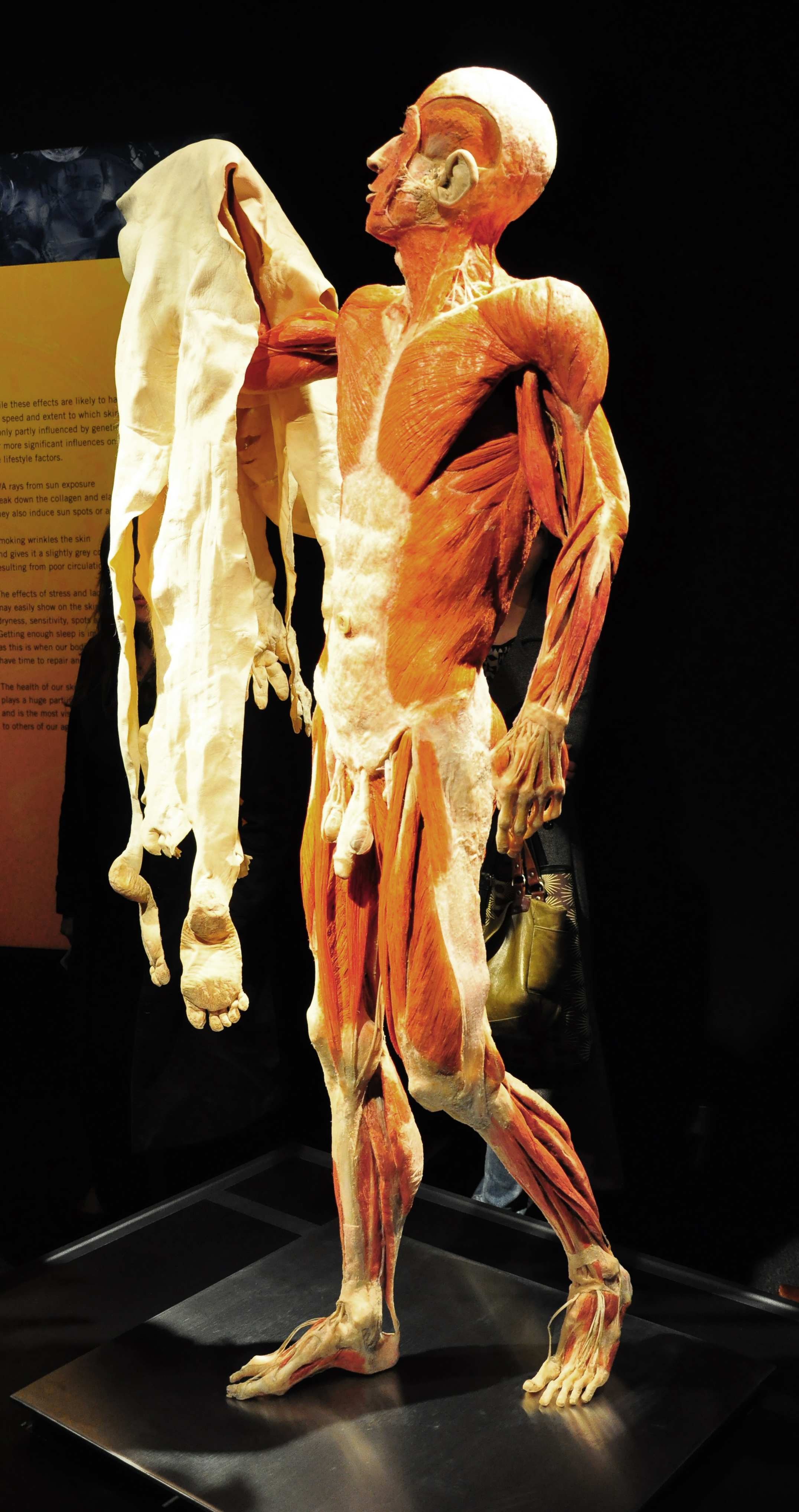

As one of the most popular exhibitions of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, Body Worlds has traveled to more than a hundred cities since 1995 and been seen by 40 million people.26 With the development of technology, Body Worlds brings a modern twist to the controversy of displaying human remains. The anatomical exhibition displays odorless and aestheticized human cadavers through a process called plastination, a technique invented by the founder of Body Worlds, the German anatomist Dr. Gunther von Hagens. Platination replaces the human body's 70 percent of fluid content with resin and silicones to harden tissues and preserve the body from decaying.27 Therefore, Body Worlds creates a much gentler environment for the public to learn anatomical knowledge compared to the anatomical theaters in early modern periods, which performs dissection in front of the public28; or the bloated, smelly corpses in glass jars filled with formalin. As stated by the exhibition catalog, it aims to present "The medical enlightenment and appreciation of lay people".29

Although Body Worlds has achieved unparalleled financial success as an educational anatomical exhibition, it has generated significant ethical concerns and, thus, controversy, particularly regarding the aestheticization of cadavers, donor consent, and the large amount of profits generated from it. Presenting himself as artist-anatomist,30 von Hagens and his Body Worlds generates contradiction by displaying cadavers with both clinical detachment and artistic fashioning, which breaks the tradition of exhibiting corpses in medical contexts.31 His whole-body plastinates are given different social identities and characteristics through the positions in which they are displayed. In order to show certain anatomical features, they are arranged as if participating in activities such as running, playing basketball or musical instruments. Some cadavers even wears earrings, mirroring living humans. As a result, these anatomical objects resemble artistic sculptures.

Mummy in a Coffin

The case of the Museum of Manchester reinforces how the collecting and display of human remains continues to generate controversy. Amongst all arguments, one of the most commonly stated reason to display mummies is their educational value. "As a university museum, the Manchester uses its international collection of human and natural history for enjoyment and inspiration. Working with people to provoke debate and reflection about the past, present and future."12 The museum's mission focuses on providing knowledge and community education, closely aligning to its collegial culture. Accordingly, mummies enable scholars, such as archeologists, anthropologists, and anatomists, to better understand the social structure and material culture of ancient Egypt and even, sometimes, to explain the cause of death. Also, as a public institution, museum staffs and scholars believes that to see these bodies is an exceptional privilege for the public. Leastwise, the display of mummies can actively combat the misleading or even disparaging stereotypes of mummies and ancient Egyptian culture in mass media. Nick Merriman, the Museum's director argued that "if unwrapped mummies are not on display, then the public's knowledge of the appearance of mummies, is likely to be misguided by the vengeful monsters portrayed in films".13 Furthermore, some scholars felt that the museum's decision to cover its mummies could damage its academic credibility. The chairman of Manchester Ancient Egypt Society Bob Partridge expressed his concerns. He called the decision to cover the mummies as "incomprehensible" and said that he hoped the decision would be reserved.14 Similarly, George L Mutter, an Associate Professor of Pathology at Harvard Medical School also criticized the covering of the mummies, claiming that "For decades, Manchester Museum has been a leader in the scientific study of human mummies, the decisions to hide the mummies from view is a step backward."15

Mummy in a Coffin

Besides the importance of mummies' educational significance, some scholars argues that respectful and ethical display of human remains can be achieved, therefore mummies can stay in exhibitions. Although human remains are not neutral objects, museums can "neutralize" them by providing them with historical contexts.18 In the official statement from the museum in attempt to create a more respectful environment, it declares that "Displays should always be accompanied by sufficient explanatory material." 19Moreover, some Egyptologists even question the inherent reason of why displaying mummies is controversial. Dr. Jasmine Day, President at The Ancient Egypt Society of Western Australia Inc. argues that objection to display of Egyptian mummies are not truly driven from the empathy with the deceased, but from unconscious psychological concerns and fears for deaths.20 In addition, he firmly believes that Egyptian mummies and other human remains would be more safely deposited in museums as ancient and historic cemeteries cannot always be left unexcavated with the urbanization and development due to the overpopulation.21

While many people advocate for the display of human remains, others demonstrate their concerns on this controversial issue. Firstly, the educational benefit of the display of mummies is being questioned. What indeed did we learn about other cultures or history by seeing human remains on view? Sociologist and Professor Hugh Kilmister at the Birkbeck, University of London states that "The answer is nothing".22 He believes that Egyptology cannot be learned simply by looking at a mummy. Instead of seeking enlightenment ideas or obtaining knowledges, we are merely looking at the dead for entertainment.23

Moreover, larger concerns regarding the display of human remains revolve around whether it is appropriate for us to deign to speak for the ancient dead and whether we can truly give them respect while violating their own wishes. Mummies and their associated grave goods were bought or exported illegally from Egypt in the 18th and 19th century, and the display or conservation is openly denying or ignoring the clear wishes of the deceased ancient Egyptians themselves. According to ancient Egyptian beliefs, the physical body was intended to stay in the tomb as their immortality is connected to Egypt, which is the animistic world.24 Ancient Egyptian texts clearly state that a person was made up of four different component parts. Ren, the name; shuyet, the shadow; ka, the double or life-force; ba, the personality or soul; akh, the spirit.25 Together, they constitute a complete individual who can enter into Afterworld. Ironically, when they were dug up and restored into museums, and even renamed by museum staffs or scholars, their wishes were disregarded. Therefore, even if we think we are treating the ancient dead with respect, the display of mummies is arguably an act of desecration.

Even though mummies are among the most common human remains collected and displayed, it is still a controversial topic sparked with fierce debates. The educational benefit of the display and whether we can truly treat them with respect remains questionable.

Body Worlds Exhibit

The most outspoken objections against this aestheticization of human bodies came from Europe, where journalists and moral theologians expressed disgust with the artistic motives displayed by the plastinated figures and by the desecration of deceased persons.32 Some medical scientists and anatomists also rejected the Body Worlds exhibitions, claiming that von Hagens violates the rigid regulation and ethical norms of the treatment of corpses by displaying them for frivolous purposes.33 In addition, directors of Europe's leading anatomical museums, such as the Anatomisch-Pathologisches Bundesmuseum and the Fragonard Museum, also responded negatively by criticizing the exhibition as "sensationalism" and denying its scientific or educational value.33 Overall, these objections argue that human bodies should be in the service of art.

In addition to the aforementioned debates, the public also worried about the source of the cadavers used in Body Worlds . Today, von Hagens actively cultivates exhibition visitors as donors, distributing body donation forms at each exhibition. Critics did, however, question the ways in which he originally sourced bodies, particularly regarding the consent of the individuals who ended up plastinated and displayed in his exhibitions. Body donations include organ donations and whole-body donations, and donors have to be clearly informed of what their bodies are going to be used for, yet it is unclear if donors consented to be displayed in any pose and to being in sold in slices. Furthermore, human right activists also attacked the exhibition as unethical for trafficking in human bodies.35 Initially, von Hagens was accused of obtaining illegal bodies of psychiatric patients and executed prisons from China.36 Later on, von Hagens stopped obtaining unethical corpses. Now his shows only contains clearly sourced donors, mainly from Europe.37 Similarly, Bodies: The Exhibition from Premier Exhibitions, which is a rival exhibition with Body Worlds from the US, also uses suspiciously illegal human bodies.38 It is undeniable that von Hagens used illicitly acquired cadavers in the past, and the controversy around donor consent remains.

Body Worlds Exhibit