Censorship: Why Are We Scared of Sexuality?

To censor artists, forcing them to conform to a certain standard of government-mandated decency, is a direct assault on the freedom of expression.1 To censor artwork is to limit freedom of speech and representation. Censorship is often used as a tool of power by the already privileged; to further silence those with opinions and experiences different from the majority. In doing so, some voices are elevated while others are left silenced. Systematic censorship threatens the representation of marginalized groups as well as individual artists' voices.2 It is the role of artists to defend the freedoms of expression even in instances that make viewers or the public uncomfortable. The artistic community functions best when it does not shy away from controversy but instead uses visual culture to foster greater engagement with and curiosity from the larger community.3 Although the specific objects or texts that are censored vary from culture to culture, the desire to repress works of art that challenge social norms or deal with controversial subject matter is ever present. A common theme amongst censored works of art, or those works which groups or individuals argue should be censored, is a challenge of socially accepted norms of sexuality. Censorship limits dialogue and discourages social and cultural progress.

One of the most famous examples of this dilemma caused massive controversy in London, enough to incite vandalism, yet did not generate the same level of hysteria when the work was displayed in New York City. Among the most famous and controversial exhibitions of the late 20th century was Sensation: Young British Artists from the Saatchi Collection, which premiered at the Royal Academy of Art in London in 1997 before traveling to the Brooklyn Museum of Art in 1999.7 While on view in London, Marcus Harvey's portrait of the child serial killer Myra Hindley caused a public outcry and generated massive publicity, albeit much of it negative, for the exhibition and the artist. Harvey recreated Hindley's mugshot in a pixelated style using a cast of a child's hand rather than a traditional paintbrush.8 When the show moved to the United States, the painting generated little to no reaction among the citizens of New York City, as they lacked the cultural or historical background to be offended by Myra and her accompanying sinister narrative. Instead, Rudy Giuliani, then mayor of New York City, attacked Chris Ofili's The Holy Virgin Mary. A practicing Roman Catholic, the British-born artist depicted a bare-breasted black Madonna adorned with elephant dung and featuring butterflies made from cutouts of female genitalia found in pornographic magazines. Giuliani was so "offended"9 by Ofili's work that he threatened to revoke the Museum's $7.3 million city subsidy if the painting was not removed.10 Giuliani, who like Ofili is a Catholic, objected to what he saw as a sexually-charged representation of the Virgin Mary. In response, Ofili countered that all representations of the Virgin, even those in London's National Gallery, are sexual.11

Perhaps no other type of artwork generates more controversy than those depicting or referencing nudity and sexuality. Compared to our European counterparts, Americans are often threatened especially by sexuality and by anything that challenges the traditional sexual roles of men, women, and children. Throughout the history of art, nudity and indecency have been continued sources of controversy.4 Take for example, when in 1886 at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts Thomas Eakins allowed female students to draw a male model in the nude. The mere presence of nudity in the company of women, who were seen as too pure and chaste to be exposed to such subjects, was enough to have Eakins removed from his prestigious post of instructor.5 However as the definitions of terms such as decency, lewd, obscene and offensive have changed; so, too, have public perceptions. Who or what is censored, and to what degree, is reflective of the contemporary political and cultural climate in which artists and their art reside.6

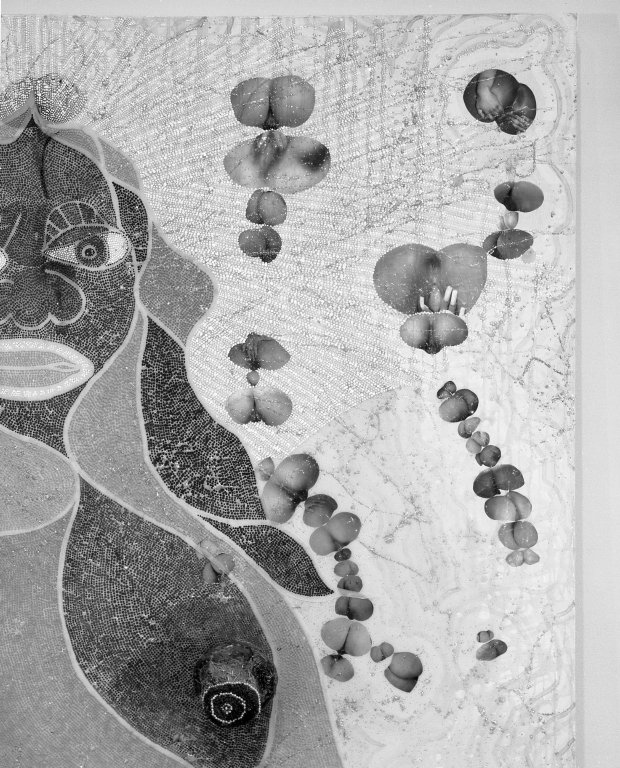

Portrait of Myra Hindley

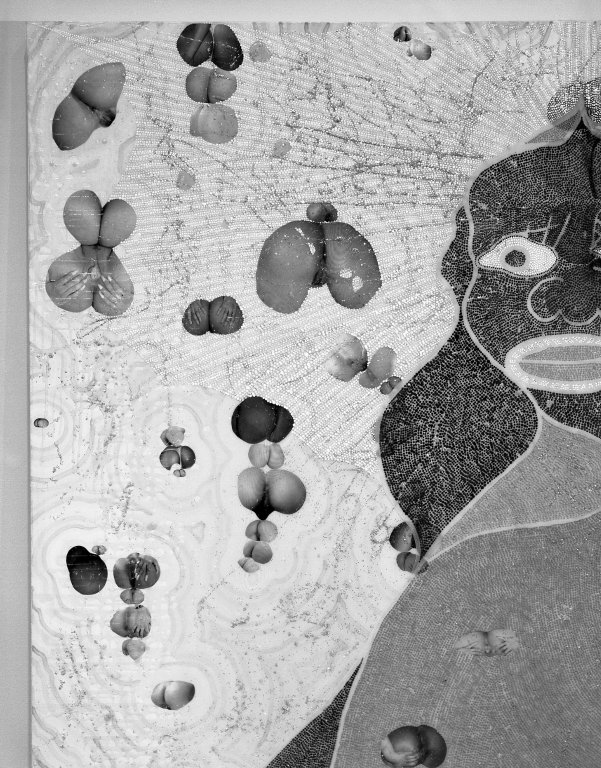

The Holy Virgin Mary

The Holy Virgin Mary